Pour la version française de ce texte, c’est par ici.

Let’s say you are fond of northern countries. That Jack London and Fridtjof Nansen (1) are your personal heroes. That you usually keep the windows open in winter because, let’s be honest, who’d want to sleep in a room over the scorching heat of 9°C ? That none of the above applies to you but, what the hell, cold is nice after all ?

(1) Never heard of the guy ? Go check him out (and read “Farthest North” while you’re at it)! Probably the ballsiest northern explorer I’ve ever read about.

Well, you’re in luck. I have the ideal place for you.

SVALBARD

Sommaire

INTRODUCTION

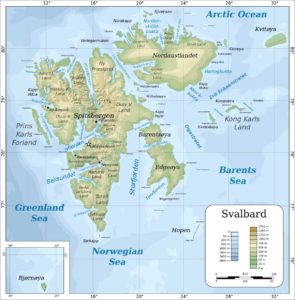

You might not be familiar with this name, but it is hard to deny that just pronouncing it out loud echoes with some cold, remote and deep northern innuendo. This is not surprising though, since « Svalbarð » literally means « cold shores » in old Norse. Even if no proof exists that a single viking set a foot there, these islands located a short hop from the north pole offer all the « Great North » aspects as they are represented in the collective unconscious.

When I say a short hop, this is not a figure of speech. Longyearbyen, the capital – and only « city » – of Svalbard is located roughly 1316 km away from the top of the world (and 766 km north from the closest Norwegian coast). For a comparison, if you walked this distance from the south pole, you would still have 300 km ahead of you in order to reach the shores of Antarctica.

This archipelago is also known under its old name as Spitsbergen, not to be confused with the main inhabited island which is also called Spitsbergen, which used to be called West Spitsbergen. And that complicated naming policy is only the tip of the iceberg (haha) regarding the strange status of this out of place, gorgeous piece of rock.

Svalbard’s history is a novel in itself, too long to explore in details here, but hella’ captivating nonetheless. Pretty similar to the the old west, it has this flair of uncharted territory only recently colonized, in the sense that the traces of the past are still perfectly visible in the open: Old mine shafts, century old fox traps, deserted cities and so on, like a life-size museum frozen in time.

Mine 2B. Abandonned and now closed to visitors, these old buildings stand still overlooking Longyearbyen

THE HISTORY OF SVALBARD

From the beginning to our days

Officially discovered by the dutch in 1596, the archipelago served as a hunting and whaling hotspot for the French, English, Danish, Russian and Dutch until 1820, when most of them moved elsewhere in the Arctic. In the late XIXth century, Norwegians realized the potential for coal mining in the area and opened their first mine in 1899, followed by English and American interests. All was good and well until some started to wonder « Who the hell this frozen-ass place belongs to anyway ? » Thus started discussions to sort this mess out in 1910, interrupted by World War I, resumed shortly after, and ending in 1920 with the signature of the Svalbard Treaty. Conclusion ? Svalbard belongs to Norway (Så fint!), but all the signatory countries were granted rights to fish, hunt, and drill in the soil like mad men (Oï..)

During World War II, a lot of surprisingly crazy stuff happened there, that you should read about if you’re curious or bored, but the situation came back to « normal » shortly after. Norway re-established its operations in Longyearbyen (the capital) and Ny-Ålesund (a northerner settlement) while the soviets opened mining facilities in Barentsburg, Pyramiden and Grumant, then closed two of them in 1962 and 1998. Overall, the situation has been quite stable since.

To close the geopolitical/history subject, Svalbard is part of Norway, but isn’t included in the European Economic Area, nor the Schengen area (that’s important. You won’t need a visa but it’s better to pack your passport when traveling there). It is not a county in itself but is administered by a governor appointed by the Norwegian government. In accordance with the Svalbard treaty, the permanent Russian settlement of Barentsburg is still a thing, despite being the last. The territory remains of strategic importance for Norway in the Arctic, especially with the receding ice sheet and opening of new possibilities around the north pole. The situation with Russia is quite stable for now, but there’s no telling what the future holds for this little polar bear nursery.

Svalbard today

This leads us to present day Svalbard. While mining is still a thing in Longyearbyen, Sveagruva and Barentsburg, Ny-Ålesund is now a research station full of worldwide scientists. Longyearbyen, still the world’s northernmost settlement with permanent population, opened up a lot to research (they have a university) and, back to the point, to arctic tourism.

The tourism industry has developed exponentially over the past 20 years, and along with it, the possibilities to discover the wilderness. Be warned, relaxing is a vague notion when it comes to spend some quality time up there and along these options, none of them are cheap. One of the reason for this is that no travelers are allowed to cross the city limits without a guide equipped with a rifle tagging along. The polar bear risk is no joke, and more importantly, if you survive an attack you’ll most likely be charged with reckless behavior once your limbs are stitched back together. All the more reason to go on an adventure within a team of professionals.

HOW TO VISIT THE PLACE ?

So now that you set your mind to it, what is the best way to wander in this lichen paradise ? You could just buy a ticket to Longyearbyen, book a room in one of the few « hotels » and go on a one or two days short trip offered by the local agencies. This is pretty good for a first contact, but the price ratio of such a trip can rapidly become overwhelming. Accommodation rate in the city are through the roof and short trips, pricey as they are, won’t take you very far inland. If you never experienced this climate, this could be a good « first touch », but if you are more familiar with arctic adventure, I would recommend something else. The all-in one packages.

This type of packages offers, in my mind, the best experience/price ratio. Several agencies around the world offer this type of holidays, including the plane ticket, housing in Longyearbyen, and several days expedition on skis, kayak, snow-shoes, hiking, or snow-mobile, while camping close or far from the city. The downsides ? These are group holiday. People traveling this far north are usually quite the merry companions, but if you are a loner type, this can be an issue. These expeditions can be rough and push you or your comrades to their limits, so tensions can rise in a group, even for a short period. Personally, I luv it, but consider yourself warned.

What about the upsides then ? Well, if I had to explain them you wouldn’t be reading this article anyway. Let’s just say that not a lot beats the feeling of quietly staring at the midnight sun while on your bear-watch, looking out for a white spot coming closer to the tents where your mates are sleeping. A splash in the fjord catches your attention and behind the baby petrels shading their juvenile feathers on the beach, you witness some Belugas gently swimming along the shore, between the sand and the small icebergs quietly drifting away. Yes, this is actually a memory, and no, absolutely not a lot beats that at all.

In Spring (consider it as Winter)

There are two main season opened for this kind of trip, spanning from early march to late September, with each of them having their preferred activities. If you are looking for a cross-country skiing adventure, spring would be the best for you. As the polar night slips away and daylight is taking over, the snow remains and covers Longyerbyen and the fjords all alike. You will be equipped with a pulka, with all the necessary equipment equally split among the participants, and either start from Longyearbyen or be dropped in the open after a chaotic trip inside a caterpillar monster.

Usually, the first option will take you along the coast with a stop in Barenstburg and/or Pyramiden, the occupied and abandoned Russian settlements. These are possibly the last places where you’ll witness the full spectrum of the post World War II soviet architectural style. Lenin statues still standing and socialist realism artwork are all over the place. Barentsburg features a hotel, a souvenir shop and some other facilities with colorful locals that will give you a taste of Russian hospitality (2). Pyramiden on the other side is a ghost city frozen in time. Abandoned not a long time ago, this is probably the eeriest place you’ll ever visit. I won’t say more since it’s a place to witness, not to describe, and since I’ve never been there but listened to the tale of other travelers, I won’t spoil it for you, nor for myself.

(2) For what I’ve been told, it is a strange mix of overwhelming genuine kindness and slavic stare of death contest.

The second option (3) will see you board a coughing, shaky, carriage mounted on caterpillars reaching the amazing speed of 20 km/h on a slope. You’ll be packed like eight hot dogs in a bun in the rear carriage, with luggages falling on you (or the opposite) while nursing the two sledge dogs hoping their nausea won’t turn into another vomit in such a confined environment.

(3) This option is the one I experienced, and its description will correlate with a trip I made on march 2015 with a specific agency. Other destinations are possible for a remote departure, so experience may vary depending on your choice of company/package.

Frankly, I loved every seconds of that experience.

For this specific trip, the devil’s machine dropped us approximately 100 kilometers away from Longyearbyen, south-east from Sassen-Bünsow Land nasjonalpark, in a roaring blizzard that buried instantly half our equipment under a good layer of snow. The goal was to reach back the city under ten days following an itinerary made of glaciers, pack ice, mountain pass and long valleys, smooth and rough terrain, immaculate mountains and giant mining areas. I can’t say it was easy. The first days were made of « short » hops since the pulkas were heavy with provisions, gradually increasing the distance as the weight decreased. We experienced blinding sunny weather, heavy snow, temperature range between -30°C and 0°C, with 0°C feeling hot as hell compared to the frozen-beard type of weather. Some days we advanced rapidly, others we had to remain on the same spot due to bad forecast or a group member feeling too weak. The itinerary evolved a lot because of that, the guide adapting the course constantly depending on the conditions.

We finally reached Longyearbyen exhausted, sun burned, craving for fresh food after a 150 kilometer trip that I will never forget. No polar bears were spotted this time, only paw-prints the size of my head, but seals and elks accompanied us quite often, and the human experience acquired was invaluable. There were moments of tension of course, but they didn’t cast a shadow on the collective experience that this trip has been. This may hardly sound like holidays, but I guarantee that this kind of experience is a forever lasting memory for the one who is adept of physical expeditions in « uncharted » territory.

In Summer

So this was the spring part. What about summer then ? Well, the landscape is not quite the same that’s for sure. Thanks to the gulf stream, Svalbard is a surprisingly temperate place given it’s latitude, with an average temperature of -14,7°C in January and 6,7°C in July, meaning that snow melts on the lower altitude, transforming the white colour sheet in a more brownish tint. So no more ski during the summer, but it’s time for kayaking to rise up.

There is a vast array of offers regarding this activity. From day trips from Longyearbyen to longer expeditions along the coast. Again, I would recommend the second option, allowing for a far deeper experience of a polar expedition. Summer also brings the wildlife back to life, with easier spotting of polar bears, arctic foxes, walrus and seals. Bird-watching is also at its peak during summer, being the reproductive period for most of the species who thought that was a neat place to raise some feathery offsprings. So remote expeditions are the best to observe wild life offspring and parents in their natural environment.

In the summer of 2012, I joined a 12 day expedition in the Kongsfjorden area, close to New-Ålesund. This trip, offering a good balance between kayaking, camping and hiking, didn’t come cheap, but again, offered an experience like no other. No weird bulldozer thingy to reach the area this time, but a 12 hour boat trip on the MS Farm, pride of the Spitzberg’s expedition vessels. This little bastard can handle the sea, I’ll give her that, but holly molly what an humbling ride. The sailor in me who always prided himself of never having been subject to sea-sickness got a reality-check real fast. Hard to enjoy the landscape when you are stuck in a fetal position, inside an overcrowded cabin full of fellow adventurers ready to barf their will to live.

Somehow, we survived. Thus started ten days of kayaking in a place too majestic to describe. Camp was mounted every two or three days, allowing us to focus on daily sails and hikes along the glaciers, inside the ice pack when its density allowed safe passage, close to the breading sites while being attacked by ferocious terns with sharp beaks, until finally eating dinner in the main tent before falling asleep in a tight sleeping bag under the midnight sun.

Speaking of the sun, one particularity of summer trips above the arctic circle is the light. Most of us are unconsciously imprinted with the fact that the sun rise in the east and sets in the west, and we usually map our surrounding with this primordial fact. Up there, the sun circles around you all day and all night, offering perspectives that feel almost supernatural. It is difficult to put words on this experience, but the majesty of the still hours of the night, bathed in light by an eerie low sun when every fibers of your body screams that this glowing round thing SHOULDN’T be in the north, is mind-blowing. Of course, this lighting effect is common to every place located under this latitude, but besides Greenland, not a lot of them offers an all-in-one fjord, glacier and mountain landscape to go with it as Kongsfjorden does.

Sadly, no polar-bear were spotted during this time either, apart from their gigantic paw marks here and there. Svalbard reindeers were numerous though, plus some arctic foxes brave enough to try and steal one of my boots. Regarding the birds, holy damn what a festival: Arctic terns, skuas, razorbills, puffins, fulmars, loons, the elusive ivory gull and much, much more could be spotted during our stay, either quietly living their life or attacking us on sight while we ran screaming. Good memories.

The trip ended with a beer in the only « pub » of New-Ålesund, surrounded by scientists either happy to see new faces, or with strong opinions about the growing tourism industry reaching such remote places so far preserved. That’s a interesting point, that I’ll develop shortly.

When the MS Farm returned to pick us up, we were split between the joy of returning to the civilization (especially the possibility of goddamn shower) and the absolute sheer terror that this puke factory represented. And puke factory it became once more, but I won’t delve into this complete loss of composure and self-respect.

For those interested, I made a short video of this adventure a few years ago, that can be seen right there.

EPILOGUE AND AFTER THOUGHT

I hope that these short accounts of my two Svalbard trip gave you a small glimpse of what can be expected from such a voyage in this absolute gem of an archipelago. Again, there are many other options available, suited for all types of tastes, from the arctic cruises close to the shore, to the snowmobile day trip or longer and so many more. Surprisingly, Svalbard is not the best place for Aurora Borealis sightings since it is actually a little too north regarding the Auroral zone. Plus, the weather is often cloudy in winter and temperature is better on continental Norway for a long stay outside in the winter night.

Now, for the more practical matters and sensible topics. Svalbard is expensive, there is no denying that. Going there on holiday is not just a proof of a polar adventure enthusiast mind, but automatically categorizes you in the privileged few percents members of society that can spare the expense of couple thousands euros/dollars on a trip not even a month long. It is an important fact to keep in mind as some (but fortunately few) people I met could be quite condescending, and frankly a little bit full of themselves, when it comes to understand this privilege. From my experience, even if the far north doesn’t appeal to everyone, many many people would love to discover it given the chance, the time, and especially the finances. The same applies to other « alternative » trips around the world, especially in the backpacking community. But this is another topic I won’t dig into just yet.

This correlates with some of the Ny-Ålesund scientists point of views I mentioned earlier. Why the hell would we open preserved lands to tourism, especially when said tourism is growing each year more and more. I understand this argument, and I don’t have a simple answer to it.

Nevertheless, I do think it is important to inform the public about urgent matters that doesn’t affect them in their daily life, such as global-warming, and Svalbard is a precious place for that. Kongsfjorden’s glaciers for example have receded at an alarming rate for the past years, and witnessing it with your own eyes is extremely valuable. Longyearbyen museum underline this issue and the subject usually comes up during conversation with locals. So I’m positive that tourism in Svalbard can play an educating role and act as a wake-up call for many.

Still, it is true that human has a bad influence on its environment (no shit Sherlock), even in a controlled area, even on a small scale. I understand that an ornithologist can be pissed off seeing a bunch of red-parka bozos taking a group picture three steps from a skua nest with the alarmed mama circling around them, desperate that those giant monkeys can’t take a clue.

So not an easy dilemma indeed. I guess we all live with our contradictions. For me, it is being a green, nature loving person, worried about global warming but seeing no problem taking a plane, one of the biggest CO2 factory, in order to witness it on site. So I guess, the price of such trip is, sadly, a good way to avoid a mass arrival of polar tourists. Even if growing, tourism in Svalbard is limited by the infrastructure and is bound to remain on a relative small scale. That means only a privileged few can witness its beauty, while still preserving it.

I can’t say it’s fair, but this is how it is. So if you happen to visit Svalbard, just remember that you are part of the lucky few. Don’t feel too bad about it, but keep that fact in mind. Respect the land, respect the limits, and when you come back, tell your friends of its beauty and how fragile it is. You will then be a privileged witness of what the nature has to offer. It’s up to you to be its guardians as well.